I had warned my parents before taking them with my French husband, Yves, and our three children to France that summer in 1987 that it was a period when Americans were in disfavor, and that they shouldn’t be too surprised to be treated with the haughty arrogance for which the French are infamous. Fortunately, that didn’t turn out to be the case, especially in Normandy where Americans will forever be viewed through different eyes.

My father was returning for the first time to an area he had previously seen only from the windows of The Crow’s Nest, the B-24 Bomber on which he had served as a radio man in World War II. Based in Britain, he flew thirty-six bombing missions over France and Germany striking against the war machine of a Nazi tyrant and assisting in the liberation of a country with which he had no personal ties at that time. In America, he had a wife who daily wondered if he would ever return, and a nine-month-old son he had never seen. The irony was that since the time he had placed his life on the line to liberate France, his ties with the country had become significant. His youngest daughter, born ten years after the War ended, married a Frenchman, and consequently his grandchildren from that marriage were half-French, and later on a grandson, (his oldest son’s son) would marry a French girl.

On our visit to Normandy, we were accompanied by my husband’s parents, who had also been deeply impacted by World War II and the consequent Allied liberation of France. Yves’ father, Roger (left above), had served in the French military during the early years of World War II, was later taken as a prisoner of war after the German occupation of France, and then was put to work by the Germans to keep the invaluable French railroads running during the Occupation. Yves’ mother, Marguerite, was conscripted to sew uniforms for the Germans in her little village of Langon in Brittany, and her only sibling, her brother Joseph, nearly lost his life in the war. She will never forget that just as American troops were advancing towards her region a group of retreating Germans, pretending to be Americans liberators, drove through the village and shot and killed a dozen cheering youth.

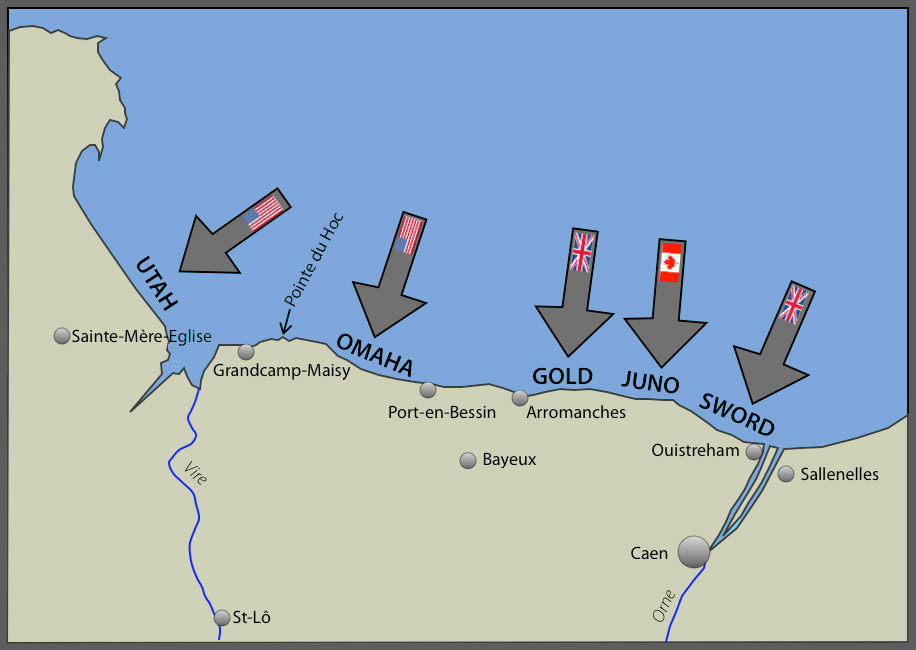

We arrived in Normandy in the evening, and made two brief stops along the Eastern flank, the British Sector, before heading for our Bed and Breakfast. The first stop was near Sword Beach, along the Orne Canal where Major John Howard led his glider-borne men of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry in a surprise attack to secure the lifting canal bridge at Bénouville code-named “Pegasus Bridge.” They took off just before 11:00 p.m. on June 5 from England and were released an hour later for the glide in to the objective, crash landing just 50 yards from the bridge. Howard’s group fired the first shots on the ground on D-Day, but secured their target by twenty minutes after midnight. The Ox and Bucks suffered the first D-Day casualty, Lieutenant Den Brotheridge, who is buried in the churchyard near the British Cemetery at Ranville. We stopped and bought postcards at a nearby café, originally belonging to the Gondrée family, which proudly advertised itself as the first French building liberated on that memorable day.

As dusk descended, we drove to the top of the bluff overlooking Gold Beach nestled between flanking cliffs below. There at that viewpoint, the British have erected a Memorial, and an earlier visitor had laid a wreath with a ribbon bearing these simple but poignant words, “To Our Fallen Comrades.” Next to that offering had been placed a packet of letters from British schoolchildren, too young to fully realize what their grandfathers had done, but nonetheless lauding the British fight for freedom on the shores of Normandy. In 1944, these same cliffs were topped with German gun emplacements that were silenced by naval bombardments from HMS Ajax on the morning of D-Day. Landings on Gold Beach took place with minimal casualties, although the weather hampered efforts to unload equipment. The beach was backed by low, marshy land where today the town of Arromanches sits, and the specialized equipment designed by the British general, Percy Hobart, affectionately dubbed “Hobart’s Funnies,” were at their most effective on Gold Beach, clearing mines and bridging ditches to speed the inland advance in the gully between the cliffs. Here, after the initial assault, the Allies established one of the two pre-fabricated Mulberry Harbors.

The concrete Gooseberries were used on all beaches as breakwaters, but at Gold, the Mulberry was a full-blown port with caissons sunk inside the ring of Gooseberries to form floating piers and roadways. This allowed the unloading of supplies from ships at all stages of the tide. Even during wartime, the Allies were concerned about permanent damage to the pristine landing beaches, and designed the installation to endure for only 100 days, but remains of the harbor survive today and were clearly visible from our vantage point forming a complete arc around the beach. On many later visits to Gold Beach at low tide, with both children and grandchildren , we were actually able to climb on the concrete caissons that are now considered as cherished historic landmarks by the people of Normandy.

The following morning was misty as we began our pilgrimage on the opposite flank, the Western-most part of the American Sector on the Cotentin Peninsula at Sainte-Mère Eglise. Here, American paratroopers and gliders had worse luck than their English counterparts. Gliders were shredded by “Rommel’s asparagus,” sharp poles placed upright in fields to discourage just such a landing, and paratroopers were dropped too early, too late, or too low from the planned drop zone during the early hours of the morning on June 6. Some paratroopers drowned in the fields around the village that Rommel had ordered flooded to defend against an airdrop, and others were live targets as they helplessly floated down into the church square. A bucket brigade of Frenchmen was dousing a blaze started by tracer fire while their German occupiers aimed their guns skyward at the billowing white targets. Private John Steele’s chute caught on the church tower, and there he stayed for several hours, playing dead while suffering from a wound to the foot. Today, an effigy of him hangs permanently on the church bell tower as a tribute to all the men of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions and as reminder of that historic event which resulted in the ultimate liberation of Sainte-Mère-Eglise. The windows of the village church, in contrast to the medieval stained glass scenes for which French cathedrals are famous, depict modern scenes of war and liberation, but in rich colors that rival even Chartres blue. We felt a sense of hushed respect as we entered the sanctuary.

The mist lifted as we traveled on to Utah Beach. Its name was doubly significant for us, not only because it is one of the two American Sector beaches, but also because we were from Utah. Here the very first Allied soldiers touched shore at 6:30 in the morning of June 6th. Protected by the Cotentin Peninsula, the sea was calm, although the strong tide swept the landing crafts south of their intended point. However, it turned out that this part of the beach was much more lightly defended than the planned landing place, and the Americans were swiftly ashore. In contrast to Omaha, the bluffs overlooking Utah Beach are not high, and soon the amphibious tanks had breached the defenses and began pushing inland to meet the paratroopers who had gathered sufficiently to secure the surrounding roads. When we later visited a nearby shop for postcards and film, the owner kindly offered me a Utah Beach lapel pin as a gift when he learned that we were from Utah and that my father had been one of the American liberators.

Between Utah Beach and the Pointe-du-Hoc lies the German Cemetery at La Cambe. It is a required stop for anyone visiting Normandy because its somber black crosses and 21,160 graves, some with unidentified remains simply marked "Ein Deutscher Soldat,"

which remind the visitor that most of these Germans did not adhere to Hitler’s Nazi fanaticism, and that they also left behind loved ones in their homeland. Many were mere boys. Yet here they lie on soil where they are not honored as the great liberators but viewed as the hated enemy. Nearly thirty years later, after having discussed this tragic fact with my daughter and her family on the way to La Cambe, our eight-year-old granddaughter suddenly asked us to pull over. Thinking she was ill, we were surprised when she started picking wild flowers along the side of the road and then told us that she wanted to place them on the tomb of a German soldier to show that someone cared. Only a child could have displayed such pure compassion and lack of guile. It was a moving experience and a somber reminder of the futility and tragedy of war.

Our emotions came to a head at the Pointe-du-Hoc. This is property that has been deeded to the American government, and except for keeping the weeds mowed, it has been left exactly as it was after extensive Allied naval and air bombardment. Though rusting barbed wire, widespread shell craters, twisted rebar and broken concrete blocks belie the fact, we felt strongly that this was hallowed ground.

Resistance information prior to the invasion had identified a six-gun German battery atop these cliffs that would have threatened the landings at both Utah and Omaha beaches. The landing there, which required scaling the steep cliffs, was assigned to the elite American 2nd Ranger Battalion under the command of Lieutenant Colonel James E. Rudder. Attempts to use ladders and ropes failed, and the cliffs had to be climbed in the face of enemy fire and hand grenades rolled down on the attackers. The tragic ironies are that the six-gun battery had not yet been installed, and some of the Ranger casualties came from friendly fire. Today, at the top of these steep cliffs, Hitler’s Atlantic Wall is still impressive.

In one of the bunkers, still solid and undamaged in spite of the bombardment, a memorial plaque to the Rangers is affixed to a wall built by the enemy. The plaque lists the Rangers who lost their lives in the assault, a full sixty percent of Rudder’s men. That morning, a popsicle stick was wedged behind the plaque with these words neatly written upon it: “To those who didn’t make it from one who did.” Our tears flowed freely.

The gray skies only reinforced the somber mood as we traveled on to Omaha Beach and the American Cemetery that today overlooks it. It would be hard to imagine a greater contrast to the Utah Beach landings short of outright failure than the experience of the troops landing at Omaha Beach. The seas were heavy that morning, and unknown to the Allies, the German 352nd Infantry Division was on exercise, thus doubling the number of defenders. Furthermore, the coastline was a formidable obstacle with 100 foot high bluffs through which only five small gullies offered a way inland. The first error at Omaha was to drop the landing craft too far offshore (nearly 12 miles), and many of the craft were swamped by the rough seas. Of the 32 tanks unloaded 6,000 yards from shore, 27 sank. Many soldiers were killed by enemy fire before they ever reached dry land. Those who did reach the beach were trapped below the bluffs, unable to create a breach. Successive waves of invaders suffered similar losses and those who made it were likewise pinned on the beach. Small groups and individuals, including a company of Rangers, and officers such as Brigadier General Norman Cota and Colonel George Taylor, organized the survivors and slowly advanced to take German positions. As evening approached, the Americans had secured a bridgehead on the bluffs. Today, tourists are warned from leaving established pathways among the same bluffs because land mines and grenades might still be present.

As we strolled among the rows of astonishingly perfectly aligned white crosses, a sense of overwhelming reverence overcame us all. The behavior of visiting schoolchildren who ran along the sidewalks and a group of giggling teens who passed around a cigarette seemed entirely inappropriate, and we moved to a quieter spot. While reading the names and states of the fallen soldiers inscribed on the backs of the markers, we reflected upon those parents, wives and children whose loved ones didn’t come home. I, for one would not be there walking upon the consecrated ground with my father if he occupied one of those 9,000 graves, nor would my husband be married to me, nor would we have those three children, whose heritage straddled both sides of the Atlantic, and who were beginning to catch a glimpse of what this pilgrimage really meant.

As we stood before the Memorial’s mosaic depiction of the air and land attacks on what has been called the Longest Day, my father pointed out where his bomber squadron was on June 6, 1944. He flew two missions that day bombing bridges, roads and railways to help isolate the Normandy peninsula and prevent German troops from easy access into the area. As his voice wavered, an elderly couple approached us and in broken English asked, “American, yes?” My husband replied in French that indeed we were Americans and that the man whom they were addressing was his father-in-law who had belonged to the American Army Air Corps playing his part in Hitler’s defeat. They took his hand with a degree of reverence and homage, shook it with deep sincerity and said, “Tank you, tank you.”

I have walked the beaches of Normandy on many occasions since that time. I have taken many friends, as well as my children and grandchildren, but I have never once visited without feeling the sacred nature of those sites. As I ponder what took place on the Beaches of Normandy that day so long ago, I realize that not only was D-Day a turning point in the war, but that it also represented a turning point for unborn generations who would follow, who might not have followed had Operation Overlord been the disaster that Eisenhower feared, or worse yet, who might have been born into different circumstances in lands where freedom was an elusive dream.

I still have and cherish the lapel pin from Utah Beach. It is a reminder of the sacrifices that men are willing to make for freedom. It is a reminder that there are times when we must take a stand against tyrants, but most of all it is a reminder of the legacy left by my father who passed away fifty-five years after that fateful day in June 1944.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed